You look up at your expensive vintage chandelier and see a layer of gray dust coating the glass. It looks terrible. You grab a wet rag, climb a ladder, and start wiping while the lights are on. Suddenly, you hear a "pop," or worse, you feel a sharp electric shock.

Cleaning LED Edison bulbs requires specific caution because the glass is thinner than standard bulbs, and the electronics in the base are sensitive to moisture. To maintain them safely, you must always turn off the power, use a dry microfiber cloth to prevent thermal shock, and avoid chemical sprays that can dissolve the adhesive bonding the glass to the metal base.

I have a customer named Jacky, who owns a chain of steakhouses in Texas.

His restaurants are famous for their rustic decor. Lots of wood, leather, and hundreds of my exposed filament bulbs.

One day, he sent me a photo of a shattered bulb.

"Wallson," he texted. "The glass just fell off the base. My janitor was cleaning them."

I asked him a simple question: "What did he use?"

"Window cleaner spray. And a heavy hand," Jacky replied.

This is the most common mistake.

People treat Edison bulbs like window panes. They are not.

Edison bulbs are delicate instruments.

First, the visual appeal of these bulbs depends on clarity.

Unlike a frosted plastic bulb where dust is hidden, an Edison bulb is clear.

The dust sits right on top of the glowing filament view.

It blocks light. It reduces the lumen output by up to 20% in a dirty restaurant environment.

But more importantly, dust is an insulator.

LEDs hate heat.

If a thick layer of oily dust covers the glass, the heat cannot escape.

The internal components get hotter.

The lifetime of the bulb drops from 25,000 hours to 15,000 hours.

So, cleaning is not just about beauty; it is about saving money.

But you have to do it without killing the bulb—or yourself.

Why Must You Never Use Liquid Sprays on the Metal Base?

We often spray Weindex or water directly onto light fixtures to clean them quickly. For sealed plastic bulbs, this is usually fine. For vintage-style glass bulbs, this is a recipe for chemical failure.

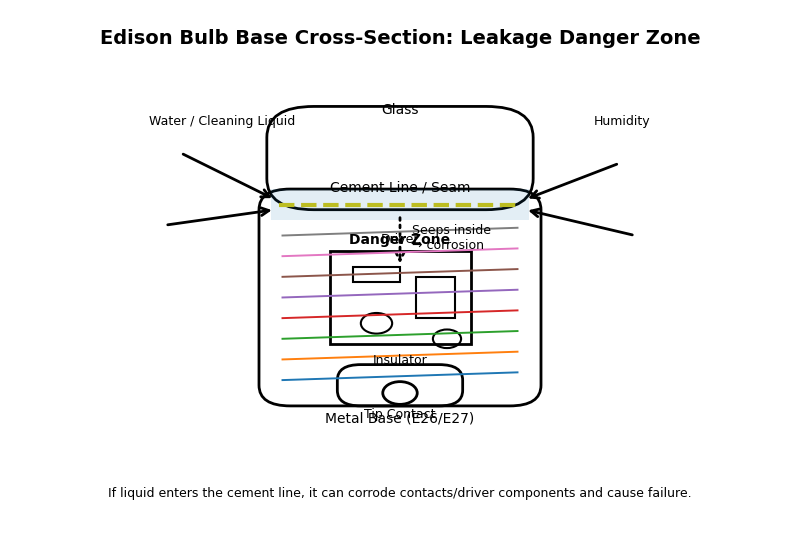

Spraying cleaning fluids directly onto an LED Edison bulb can cause the liquid to seep into the gap between the glass and the metal screw base (the E26 cap). This moisture can short-circuit the driver electronics inside or dissolve the cement glue that holds the glass globe in place, causing the bulb to separate.

Let me explain how we build these bulbs in the factory.

We take the glass shell. We take the metal base.

We join them together with a special high-temperature cement glue.

This glue is strong, but it is not waterproof.

If you spray a chemical cleaner—especially one with ammonia or alcohol—onto that joint, it eats the glue.

Over time, the bond weakens.

Then, gravity takes over.

One day, the glass simply falls off, leaving the live wires exposed.

The Short Circuit Risk:

Even worse is the electronics.

Remember, the "driver" (the computer chip) sits inside that metal cup.

It is not sealed like a submarine.

If water trickles down the side of the glass and enters the base, it touches the circuit board.

This causes corrosion.

Next time you turn the light on—Spark. Fart. Dead.

The Right Way:

Never spray the bulb.

Spray the cloth.

Dampen a microfiber cloth slightly with water or a mild alcohol solution.

It should be damp, not wet.

If you squeeze it, no water should drip out.

Wipe the glass only.

Stop 2 centimeters before you reach the metal base.

Use a dry Q-tip or a dry brush to clean the metal threads if they are dusty.

Keep liquids far away from the electrical contact points.

The "Thermal Shock1" Factor

Another reason to avoid wet rags is physics.

Glass expands when hot. It shrinks when cold.

Edison bulbs run cooler than old tungsten bulbs, but they still get warm (around 40°C - 60°C).

If you take a cold, wet rag and touch a hot glass bulb?

The temperature difference creates stress.

The glass can crack instantly.

This is called Thermal Shock.

Always ensuring the bulbs have been OFF for at least 15 minutes before you touch them.

This protects the glass, and it also protects your fingertips from getting burned.

The Grease Problem in Kitchens

For my clients like Jacky (restaurants), dust is not the enemy. Grease is.

Cooking oil floats in the air.

It lands on the bulbs. It creates a sticky layer.

Dust sticks to the grease. It turns into a tar-like substance.

A dry cloth will not remove this. It just smears it.

In this specific case, you need a degreaser.

But you must use the "Spray the Cloth" technique.

We often recommend a mix of 50% water and 50% isopropyl alcohol.

The alcohol cuts through the oil and evaporates quickly, leaving no streaks.

Do not use soapy water. Soap leaves a film that looks hazy when the light turns on.

| Cleaning Agent | Safety Level | Effectiveness on Dust | Effectiveness on Grease | Risk to Glue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Microfiber | Safe | High | Low | None |

| Feather Duster | Safe | Medium | None | None |

| Water on Cloth | Medium | High | Low | Low |

| Glass Cleaner Spray | Dangerous | High | Medium | High |

| Isopropyl Alcohol2 | Medium | High | High | Medium |

We know how to clean the glass. But what about the socket? Sometimes the problem isn't the bulb, but where it lives.

How Can Corrosion in the Socket Kill Your New Bulbs?

You buy a brand new, high-quality bulb. You screw it in. It flickers or burns out in a week. You blame the manufacturer. But often, the killer is hiding inside the ceiling fixture itself.

Corrosion or rust on the socket contact points creates high electrical resistance, which generates excess heat and unstable voltage. To maintain your lighting system, you must inspect the brass tabs inside the socket for oxidation and clean them with a specialized contact cleaner or a dry abrasive pad (with power off) to ensure a solid connection.

The relationship between the bulb and the socket is like a handshake.

It needs to be firm and clean.

If the handshake is weak, power doesn't flow smoothly.

This creates "arcing" (tiny sparks).

Arcing creates heat. Heat kills LED drivers.

The "Green" Death:

In humid environments—like bathrooms, outdoor patios, or coastal homes—brass oxidizes.

It turns green or black.

This oxide layer acts like a wall. It blocks electricity.

The bulb works harder to pull current through that wall.

This stresses the driver components.

How to Check:

Once a year, during your cleaning routine, unscrew the bulb.

Take a flashlight. Look inside the socket.

Is the little tab at the bottom shiny gold/brass? Good.

Is it dull, black, or crusty green? Bad.

How to Clean the Socket:

IMPORTANT: TURN OFF THE MAIN BREAKER. Turning off the switch is not enough.

You are sticking your finger into a power outlet. Be safe.

Use a product called Electrical Contact Cleaner. It comes in a spray can with a straw.

Spray a little on a Q-tip (cotton swab).

Rub the contact points inside the socket.

If the corrosion is hard, use a small piece of high-grit sandpaper (like 1000 grit) glued to the end of a pencil eraser.

Gently polish the metal tab until it shines.

Let it dry completely before turning the power back on.

This simple 2-minute job can double the life of your bulbs.

The "Over-Tightening3" Mistake

While we are talking about sockets, let's talk about mechanical damage.

Many people think "tighter is better."

They screw the bulb in until it won't move.

This flattens the contact tab at the bottom of the socket.

Eventually, the tab gets pushed down so far it doesn't touch the next bulb you put in.

Or, you apply so much torque that you twist the metal base of the bulb separate from the glass.

The "Two-Finger" Rule:

Screw the bulb in using only your thumb and index finger.

When you feel resistance, stop.

Give it just a tiny nudge more (maybe 10 degrees). That is it.

If the bulb lights up, it is tight enough.

Do not crank it like a car wheel lug nut.

Why Are "Fingerprints" the Enemy of Halogen, but also Bad for LED?

We all know you shouldn't touch a halogen bulb because the oil from your skin causes it to explode. While LEDs don't explode from skin oil, fingerprints are still a major maintenance issue for performance and longevity.

Oily fingerprints on an LED Edison glass envelope create "hot spots" where heat cannot dissipate evenly, potentially causing stress cracks over time. Furthermore, these smudges refract light, creating ugly shadows and glare that ruin the aesthetic purpose of an exposed filament bulb.

In the halogen days, skin oil would boil on the glass surface (which reached 200°C+).

This temperature difference would shatter the quartz.

LEDs run cooler (40-60°C).

So, if you touch an LED bulb, it won't explode immediately.

This makes people lazy. They handle bulbs with bare, greasy hands.

The Heat Trap:

Even at 60°C, thermal management is key.

A thick fingerprint is a layer of oil.

Oil holds heat.

It creates a localized hot spot on the glass.

Over thousands of heating and cooling cycles (turning the light on and off), this uneven stress weakens the glass structure.

We use very thin glass for Edison bulbs to keep them clear and vintage-looking.

Thin glass does not like uneven heat.

The Optical Failure:

Edison bulbs are bought for their looks.

You are paying for the clear, crisp view of the yellow filament.

A fingerprint looks like a smudge on a camera lens.

It scatters the light.

Instead of sharp, clean lines, you get a foggy, dirty glow.

The White Glove Solution:

In my factory, no worker touches a finished bulb with bare hands.

We wear white cotton gloves.

I send a pair of these gloves to Jacky for his maintenance staff.

"Use these," I tell him. "It looks professional, and it keeps the bulbs pristine."

If you don't have gloves, use a clean paper towel to hold the bulb while screwing it in.

If you accidentally touch the glass?

Wipe it immediately with that microfiber cloth we talked about earlier.

Inspecting for "Clouding4"

During your maintenance, look for Clouding.

This is a white, milky film that appears inside the glass.

You cannot clean this off. It is inside.

This means the bulb has a small leak. Air has gotten in.

Or the chemicals in the driver are "outgassing5" due to overheating.

If you see a cloudy bulb, replace it.

It is about to fail.

It is better to change it on your schedule than to have it die during a dinner party.

Conclusion

The beauty of an Edison bulb is its transparency, but that is also its weakness. It hides nothing—not dust, not grease, and not fingerprints. By adopting a "Dry Clean Only" policy for the glass using microfiber, inspecting your sockets for the green rust of corrosion, and always handling new bulbs with gloves or cloth, you ensure that your investment lasts. Treat these bulbs like wine glasses, not like tires, and they will glow perfectly for years.

Understanding Thermal Shock is crucial for safely handling glass bulbs, preventing cracks and ensuring longevity. ↩

Exploring the effectiveness of Isopropyl Alcohol can enhance your cleaning techniques, ensuring a streak-free shine on your bulbs. ↩

Understanding the consequences of over-tightening can help you avoid costly mistakes and ensure proper bulb function. ↩

Understanding the causes of clouding can help you prevent bulb failure and ensure optimal lighting in your home. ↩

Learning about outgassing can provide insights into bulb longevity and performance, helping you make informed decisions. ↩